As I came to know more and more about film in my teenage years and to understand that there were some films that were considered classics and some directors who were considered to put out classic film after classic film, I came to look for certain films on television and at second run theatres, the latter after I went up to university.

There were several films that I wanted to see that were hard for me to find so they became films I really wanted to see. After I became interested in the work of Howard Hawks, for instance, I looked especially hard for Howard Hawks’s Ball of Fire (I was also, by this time, an appreciator of the work of Barbara Stanwyck and made every effort to watch any film with her in it) and Twentieth Century, both of which I was finally able to see if only once on television. And I looked especially hard for John Ford’s The Searchers, which I too was finally able to see on television in those dark age days before the advent of the VCR and later the DVD. Blu ray, and 4k disc.

The first time I saw The Searchers I was unimpressed. At the time I chalked my moderately negative attitude towards the film up to the very high expectations I had for the film given its critical reputation. The second time I saw the film—again if memory serves on television, on television in the days where widescreen VistaVision films like The Searchers were sadly and badly shrunk into the academy frame doing injustice to it—I was much more impressed with the film and could understand why many considered it not only a classic but one of the best films ever made, something made flesh by the Sound and Sight poll of filmmakers and film critics of their favourite films. It is still number 13 in the most recent poll of 2022, an iteration of the poll that bears the marks of a greater attention to female filmmakers.

The third time I saw the film was this week. I watched it on DVD this time around, the Warner Brothers (easily the worst studio producer of DVD’s on the market) “Ultimate Collector’s Edition” DVD of the film, a DVD which is in the correct aspect ratio but which doesn't sadly gives viewers the option of listening to the film's soundtrack in the original mono, something any quality producer that cares about history (fat chance these days) would give us. The film looked pretty good in DVD format though the reviewer of the transfer of the film at the wonderful DVDBeaver found it somewhat wanting. The “Universal Collector’s Edition” was accompanied by a lovely reproduction of the comic book produced for the film’s marketing campaign and some lovely reproduced theatre cards, both of which made the lack of a mono track and the good but not great transfer even more annoying. Anyway, the third time I watched the film, this time during my John Ford film festival, I responded more to the film as a historian and a social scientist than as a fanboy or fangirl. I ended up finding it interesting and appreciated it as a consequence particularly for what it told us about the cultural contexts of the era in which it was made.

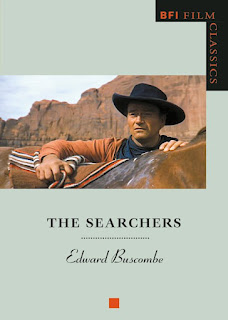

Seeing the film again stimulated me to read, Edward Buscombe’s monograph on the film, The Searchers (London: BFI, BFI Film Classics series, 2000). The monograph follows the same strategy as Western film specialist Buscombe’s excellent monograph on another John Ford film, Stagecoach. Buscombe, while he is summarising and analysing the meaning of the film text, takes readers on a journey into the production, distribution, and exhibition of the film just as he did in is monograph on Stagecoach. The only major difference between what Buscombe did in that monograph and what he did in his monograph on The Searchers was that in The Searchers he made greater use of psychoanalytic theory, something Buscombe deems appropriate in a film impacted by the social, cultural, and psychological darkness of American film noir, something that also impacted, as Buscombe notes, the Westerns of director Anthony Mann—the director of several of my favourite Westerns, a genre I am not as into as I was when I was younger—who directed film noirs before he directed Westerns and it shows. As such, the utilisation of psychoanalytic approaches to literary and film art makes more sense than its fetishisation by many contemporary film scholars given its increasing impact on American intellectual culture in the post-World War II era.

For some reason, a reason I can’t precisely put my finger on, I preferred Buscombe’s monograph on Stagecoach to his monograph on The Searchers. Perhaps it was the fact that the first time Buscombe’s approach seemed sensible if not revelatory while the second time it appeared somewhat repetitive particularly since I read both monographs one after the other in a short period of time. That said, I had and have no doubt that like Buscombe’s monograph on The Searchers, like his monograph on Stagecoach, should be mandatory reading for anyone interested in the film, in the work of John Ford, and in the history of American film.

Did Buscombe, who claims that The Searchers is one of the greatest of films ever made, convince me that The Searchers was one of the greatest films ever made? No. It is, however, as Buscombe notes, interesting for its magnificent compositions, something Ford was expert at, for its use of Monument Valley as a character, for Ford's meaningful punctuations of the film with significant camera movements, and for its noirish and almost nightmarish portrayal of American racism embodied by John Wayne’s character Ethan (Ford’s sympathies seem to lie with Marty, the “half breed” character Jeffrey Hunter plays), and for its somewhat “fakish" fairy tale ending. Just as Buscombe’s book on The Searchers is worth reading the film is definately worth watching. Perhaps it and the book on it can teach us a little something about American myths, American legends, American racism, and American imperialism.

No comments:

Post a Comment