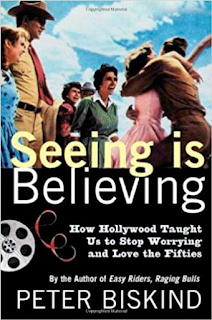

In the modern and postmodern eras the media has become an important if not the most important secondary socialiser particularly in core Western countries. Peter Biskind's Seeing is Believing: How Hollywood Taught Us to Stop Worrying and Love the Fifties (New York: Henry Holt, 1983) explores how the films of the centre (corporate liberal or pluralist and conservative) and those of the left and the right fought over the ideological terrain of 1950s America.

Drawing on and supplementing such seminal texts of the era as William Whyte Junior's The Organization Man, the Daniel Bell edited collection The Radical Right, and David Reisman's, Nathan Glazer's, and Reuel Denny's The Lonely Crowd, Biskind explores the 1950s ideological battle in films like the corporate liberal Twelve Angry Men, war films like the conservative centrist film From Here to Eternity, Science Fiction films like the right wing Invasion of the Body Snatchers, corporate liberal public enemy films like On the Waterfront, juvenile delinquent corporate liberal films like The Blackboard Jungle, left wing American Indian films like Apache, right wing Nietzschean romances like The Fountainhead, and left wing romances like All that Heaven Allows.

In order to ascertain the ideological terrain of fifties films Biskind asks a series of questions about the films he writes about. Who, he asks, is happy in these films? Who falls ill? Who dies? Who recovers? Who looses everything? Who pays and why? Who is in the driver's seat, men or women? Do women wear their hair up or down? Do women have a career or do they run the house? Is the family broken or whole? Who is absent, mom or dad? Is the family matriarchal or patriarchal? Who knows best, mom or dad? Who educates the kids, mom or dad or do the kids tell their parents what's what? Is junior a mama's boy of a daddy's boy? Is junior following in mom's footsteps or dad's? Which is dominant, culture or nature? Who dominates the coalition of the centre, scientists or soldiers/police? Is society portrayed from the top down or from the bottom up? How are reporters and citizens treated? Who saves the world, groups or individuals? Are the scientists Tellers or Oppenheimers? Who is the alien? Does the alien come to cities or rural areas? Is the alien animal, vegetable, or mineral? Is the alien us or is it them? What and who does the alien stand for? Are the aliens external or internal, are they from outer space or are they gangsters, communists, juvenile delinquents, or minories within? Who deals with the alien, the government or locals? Is social control used to control the alien or not?

Once we have answered these questions, Biskind argues, we can then categorise and classify films, particularly western and science fiction films ideologically, as films, in other words, of the consensual centre (corporate liberal or pluralist and conservative), the right, and the left. Corporate liberal or pluralist films, Biskind argues to take one answer to the questions posed, emphasise science and technology and make heroes of its scientists. Conservative films, one the other hand, tend to, and again to take one answer to the posed questions, praise the forces of order and make heroes of its professional soldiers and cops. Left wing films, to take one answer to the questions posted, tend to break down the us versus them binary and side with and try to understand the alien, us, while right wing films, to take another answer to one of the questions posed, tend to make heroes of those seeking revenge and to valorise individualism.

Many may appreciate Biskind's contention that the age of consensus, 1950s America, was not as consensual as some polemicists and apologists, and even some scholars, have made it out to be. Some may be concerned that Biskind focuses almost exclusively on the films he explores and does little in the way of archival work. Some may be concerned that Biskind does little in the way of trying to ascertain how contemporary audiences and critics reacted to the films they saw. Still Biskind's book is fascinating and enlightening and I recommend it to anyone interested in politics, ideology, and American film. Highly recommended.

No comments:

Post a Comment