I have long had an intellectual interest in religion and religious groups like the Quakers, the Mormons, and White American evangelicals. My academic career, in fact, reflects these interests. I have a B.A. in Religious Studies, an M.A. in Cultural Anthropology, and a Ph.D. in History. I wrote my master's thesis on Quakers. I wrote my doctoral dissertation on Mormons.

My interest in religion and religious groups, particularly religious oriented social and cultural movements, is not purely grounded in an interest in religion and religious groups per se. I have long had an interest in culture and ideology and how culture and ideology create and continually recreate socially and culturally constructed realities. There seems no better place to look at how culture and ideology creates reality than in religious groups. One can readily see the role culture and ideology plays in the construction of reality and identity in the history of White American evangelicalism.

There have, of course, been several books that have explored the history of White evangelicalism since the 1960s when they reemerged out of their self-imposed wilderness and became an important fraction of American conservatism and America's post Jim Crow conservative party, the Republican Party, most notably George Marsden's Fundamentalism and American Culture: The Shaping of Twentieth-Century Evangelicalism, 1980 to 1925 and Joel Carpenter's Revive Us Again: The Reawakening of American Fundamentalism, both published by Oxford University Press. There has, however, been a dearth of books on the history of American White evangelicalism generally. D.G. Hart's That Old Time Religion in Modern America: Evangelical Protestantism in the Twentieth Century (Chicago: Ivan Dee, 2002) attempts to fill that gap.

There is so much to like and admire about Hart's book. Hart explores, both emically and etically, how America's White evangelicals tended to want to make the world look like the church and simultaneously tended to want to make the church look like the world, a contradiction, as Hart notes, at the heart of White evangelical culture that has structured White American evangelicalism's history of seemingly endless and repeating cycles of worldliness and separation from the world, of not yoking themselves to unbelievers and of trying to make America into the image of itself. Hart's book explores the evangelical fetishisation of the Bible. It explores the evangelical fetishisation of modern American nationalism and ethnocentrism. It explores the evangelical fetishisation of modern American capitalism. It explores how White evangelicalism became the unofficial official religion of America from the 19th century to the mid-twentieth century when immigration turned the US from a WASP nation into a more religiously, ethically, and culturally diverse nation. It explores the inability of America's White evangelicals to come to grips with America's increasing ethnic, cultural, and religious diversity after 1965. It explores American White evangelicalism's modern traditionalism and traditional modernism.

For anyone looking for a wonderfully written and very readable history of White American evangelicalism, this is the book. For anyone looking for an exploration of the role White American evangelicalism has played in American history, American culture, and American politics, this is the book. Highly recommended.

Where I, Ron, blog on a variety of different subjects--social theoretical, historical, cultural, political, social ethical, the media, and so on (I got the Max Weber, the Mark Twain, and the Stephen Leacock in me)--in a sometimes Niebuhrian or ironic way all with an attitude. Enjoy. Disagree. Be very afraid particularly if you have a socially and culturally constructed irrational fear of anything over 140 characters.

Sunday, 29 April 2018

Friday, 20 April 2018

The Books of My Life: The White Separatist Movement in the United States

I have long been fascinated by a number of things, too many, in fact, something that has made my academic sojourn far more complicated and far longer than it had to or needed to be. Three of the things I have long been interested in are social movements, culture wars, and the role both play in identity and community construction. This is why I picked up and eventually read Betty Dobratz's and Stephanie Shanks-Meile's wonderful book The White Separatist Movement in the United States: "White Power, White Pride" originally published by Twayne in 1997 and republished by the Johns Hopkins University Press in 2000 with a new preface.

There were several things about Dobratz's and Shanks-Meile's book I really admired. I liked the fact that Dobratz and Shanks-Meile engaged in both emic and etic analysis. I liked the fact that they explored the White separatist movement from the inside by reading movement literature and talking to movement members. I liked the fact that Dobratz and Shanks-Meile let activists speak for themselves providing readers with a glimpse, in the process, into the diversity of the White separatist movement, a diversity that the sensationalist driven media invariably misses. I liked the fact that Dobratz and Shanks-Meile explored the White separatist movement from the outside by engaging social movement theory. Finally, I liked how informative, enlightening, and prescient the book is particularly from the vantage point of Trump America.

I highly recommend Betty Dobratz's and Stephanie Shanks-Meile's The White Separatist Movement in America to everyone now that Trump is president of the United States and, as a result, many groups and individuals in the White Separatist movement have come, so to speak, out of the closet. My only reservation is that for the general reader the material in each chapter on social movement theory and the White separatist movement may be a hindrance rather than a help in reading this excellent book. Please don''t let it stop you from doing so.

There were several things about Dobratz's and Shanks-Meile's book I really admired. I liked the fact that Dobratz and Shanks-Meile engaged in both emic and etic analysis. I liked the fact that they explored the White separatist movement from the inside by reading movement literature and talking to movement members. I liked the fact that Dobratz and Shanks-Meile let activists speak for themselves providing readers with a glimpse, in the process, into the diversity of the White separatist movement, a diversity that the sensationalist driven media invariably misses. I liked the fact that Dobratz and Shanks-Meile explored the White separatist movement from the outside by engaging social movement theory. Finally, I liked how informative, enlightening, and prescient the book is particularly from the vantage point of Trump America.

I highly recommend Betty Dobratz's and Stephanie Shanks-Meile's The White Separatist Movement in America to everyone now that Trump is president of the United States and, as a result, many groups and individuals in the White Separatist movement have come, so to speak, out of the closet. My only reservation is that for the general reader the material in each chapter on social movement theory and the White separatist movement may be a hindrance rather than a help in reading this excellent book. Please don''t let it stop you from doing so.

Wednesday, 18 April 2018

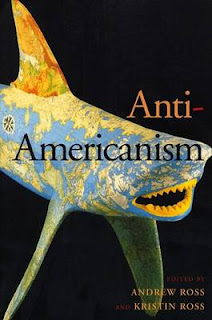

The Books of My Life: Anti-Americanism

Once upon a time I was a Biblical Studies major. I was less interested in the theology or dogma surrounding the Bible, however, than its history and its prehistorical and historical contexts. Little did I know when I switched from Biblical Studies to the social sciences that I would still be reading theological and doctrinal works and dealing, in my teaching, with theology and dogma on a fairly regular basis in my history and history of television classes.

Several years back I read Hungarian born sociologist Paul Hollander's book Anti-Americanism: Critiques at Home and Abroad, 1965-1990, published by the American arm of the venerable Oxford University Press in 1992. Hollander's book proved less an analysis of anti-Americanism than a dogmatic and doctrinal study of, what Hollander called, irrational anti-modernism and irrational anti-capitalism. In Hollander's world, anti-Americans weren't reacting to what imperial America did. They were irrationally reacting to what America was, modern and capitalist, and were thus a primitive throwback to an earlier period of world history. Needless to say Hollander's book is part of the same ahistorical fabric as the contention of American demagogues that America's enemies hate it not for its policies and global actions, but for its "freedoms" and "liberties", things that are, for demagogic purposes, suitably ideological and emotional so that the masses can be easily manipulated by demagogic rhetoric.

Recently I read another book on anti-Americanism, Andrew Ross's and Kristen Ross's edited collection Anti-Americanism published by NYU Press in 2004. Ross's and Ross's collection, which originated out of a conference held in February of 2003, is everything Hollander's book isn't. It is, in other words, less theological, less doctrinal, and more empirical and historical. I found a number of the essays in Ross's and Ross's collection interesting and enlightening. Historian Greg Grandin's essay helpfully typologises various forms of anti-Americanism. Kristen Ross's essay explores elite and more popular forms of anti-Americanisms in France. Timothy Mitchell's essay on anti-Americanism in the Middle East is particularly enlightening on how the United States has used war and radical Islamist groups to try to gain imperial traction in the Middle East and to try to stave off socialism in the Middle East. Mary Nolan's essay explores the history of post-war German anti-Americanism. John Kuo Wei Chen's essay explores elite America's use of the claim of anti-Americanism to demonise the "other". Linda Gordon's essay explores the iron cage of anti-Americanism that America's conservative apologetic and polemical elite and intellectuals have caged liberals and the left in. All of these essays show what should be obvious to any dispassionate observer, that the vast majority of forms of anti-Americanism are a rational response to post Spanish-American war imperialism.

Personally, I have long seen anti-Americanism as similar to something I researched for several years, the claim among intellectual Mormons that all criticism of Mormonism was and is grounded in stereotypes and caricatures of Mormons. It is true that some varieties of anti-Mormonism are grounded in stereotypes and caricatures. Evangelical Ed Decker's various attacks on Mormonism, most notably his attacks on Mormons and Mormonism in The God Makers, is filled with an irrational hatred of Mormons and the Mormon faith. The Tanner's many tomes on Mormonism are also problematic given that they apply methods to the analysis of Mormonism that they would not apply to their own evangelicalism because the results would be the same. There are, however, also valid criticisms of Mormonism. One can readily, for example, argue, on empirical and historical grounds, that the Book of Mormon provides the answer to virtually every quandary in 19th century American religion and so is probably a product of 19th century America. This latter is simply not anti-Mormonism, though you don't have to be Michel Foucault to understand why Mormon apologists and polemicists might want to categorise it as such or to understand why America's elite and their polemical and apologetic courtier intellectuals, like Paul Hollander, might want to categorise any criticism of America as irrational and backward and demonise it.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)