In the wake of World War II the USA and the USSR emerged as the world's only remaining great powers left standing. Though they had helped win the war together they never really trusted one another. The US had a history of anti-leftist and anti-Bolshevik ideology that stretched back to the October Revolution and World War I. The Soviet Union had been invaded by the USA along with others just after World War I and saw the US as the embodiment of late capitalism and capitalist imperialism and saw the US as a threat to the survival of Soviet communism.

In the wake of World War II with tensions between the two great powers on the rise again a culture of anti-communism which saw the USSR as the very embodiment of the communist threat was on the rise again. This anti-communist culture was grounded in manichean antinomies. For many Americans and many elite Americans the USSR was a "totalitarian" land of terror where the powers that be brainwashed their subjects and kept them in metaphorical and actual chains, the very opposite, of course, of the "free" and "democratic" United States.

This manichean tale of good and evil, good "democracies" and capitalists and evil "totalitarians" and "commies" was never, of course, accepted by all of the American population anymore than the manichean tale of a predatory US was accepted by all Soviets. Some Americans of the more apologetic as opposed to polemical persuasion, for instance, saw the Soviet Union as an expression and embodiment of a utopia to come. Additionally, in the wake of the countercultural florescence of the mid 1960s and 1970s some American academics began to break with the dominant manichean tale of good and evil that was dominant Sovietology in the US. Sheila Fitzpatrick's Everyday Stalinism, Ordinary Life in Extraordinary Times: Soviet Russia in the 1930s (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999) is one of the many books that attempts to replace the manichean and polemical passion play approach to the USSR with an empirically grounded one.

Fitzpatrick's book, like reality, is more complex and nuanced than those of either the apologetic or polemical manichean schools. Fitzpatrick lets the facts of urban life in Russia during the 1930s do the talking, facts derived from Soviet archives opened after the fall of communism and the rebirth of Russia. In eight heavilly documented chapters Fitzpatrick explores the omnipresence of the Soviet state, the shortages common during the era, how the Russian urban population dealt with these shortages, the utopian ideology of coming plenty that was at the heart of utopian Soviet culture, the situation of outcasts in urban 1930s Russia, the impact of the power of the state and shortages on Soviet families in urban Russia of the 1930s, the attempt by the Soviet state to make new Soviet men and women in urban Russia in the 1930s, state surveillance and denunciations in urban Russia in the 1930s, and the impact of periodic purges against the privileged of the "old regime", the "bourgeoisie", "kulaks", and eventually Soviet officials and the Soviet intelligentsia in 1930s urban Russia.

What struck me while reading Fitzpatrick's book was how much Soviet culture, like national cultures in general--see the civil or civic religion of the US, for instance--were and are meaning systems, meaning systems akin to another meaning system, religion. The Soviet state had its sacred mission, it preached the gospels of a radiant future of plenty and Soviet communism as the end of history as humans knew it with a missionary zeal. It had its own symbols and rituals such as the red flag, the Internationale and May Day. It had its sacred scriptures such the writings of Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, Vladimir Lenin, and Josef Stalin. It had its sacred catechism, the Short Course of the History of the Communist Party of the USSR. It had its heroes such as its Stakhanovites and the heroes of a variety of socialist realist novels. It had its heretics and demons including "foreign counterrevolutionaries", the "bourgeoisie", "kulaks","wreakers", and "enemies of the people". It even had its millenarianism, the golden age that would bring in the radiant future with its Edenic plenty.

Very highly recommended. The best book on Stalinism I have read.

Where I, Ron, blog on a variety of different subjects--social theoretical, historical, cultural, political, social ethical, the media, and so on (I got the Max Weber, the Mark Twain, and the Stephen Leacock in me)--in a sometimes Niebuhrian or ironic way all with an attitude. Enjoy. Disagree. Be very afraid particularly if you have a socially and culturally constructed irrational fear of anything over 140 characters.

Monday, 30 July 2018

Tuesday, 24 July 2018

Musings on the Film "Love Finds Andy Hardy"

I watched the fourth film in the Adventures of Judge Hardy's Family or the Hardy Family Pictures series, a serial of sixteen films released by MGM between 1937 and 1958, today. I didn't find Love Finds Andy Hardy (1938) to be a great film and I certainly wouldn't really want to watch it again. I did find it an interesting film, however.

1. There are a several cultural antinomies or binaries at the heart of Love Finds Andy Hardy. The first is the antinomy between small-town Carvel and big city New York City, which is mentioned but never seen in the film. It will be in a later installment in the Andy Hardy series. There is the binary between the historical past of Judge Hardy (Lewis Stone) and the historical present of Andy Hardy (Mickey Rooney). Judge Hardy's more traditional world is a world without aeroplanes, a world of covered wagons, a world where you don't buy on credit, and a world of correct speech. Andy's modern world is a world of aeroplanes, of cars, of buying on credit, of telegrams, of telephones, of ham radios, and the latest in hip popular speech. There is the antinomy between Andy's girlfriend Polly (Ann Rutherford), the Midwest every woman who is economic with her kisses, who swims with Andy, and who takes the long way home through the woods with Andy, and Beezie's (George Breakston) girlfriend, who Andy is looking after while Beezie is away, Cynthia (Lana Turner), who, as Andy says, wants to kiss all the time, who doesn't go swimming because she doesn't want to ruin her hair, and sees the long way home as an excuse to kiss some more. There is the binary between the uppitiness of Cynthia and the Midwest down homeness of small town Polly.

2.Betsy (Judy Garland) is the youngest of the three loves who find Andy Hardy. Betsy is, as she says, the in-between girl, the unglamourous girl. She is too young for Andy to take seriously as a love interest though clearly Betsy is smitten with Andy knowing about him before she even arrives in Carvel from the big city. Betsy becomes a "Cinderella" in Carvel, becomes a kind of grown up in Carvel, thanks to the grown up gown she wears to the Christmas Eve dance Andy takes her to and her acceptance by others at that dance during which she performs two songs with the band and gets to lead the grand march at the Christmas Eve dance.

3. Betsy, the in-between girl, is the girl who makes everything right for Andy by film's end. Love Finds Andy Hardy is a comedy of manners and misunderstandings. It is Betsy who sets the misunderstandings right by film's end. She convinces Cynthia that the car Andy is going to take her to the Christmas Eve dance in is a jalopy, a jalopy that is below the uppity Cynthia, so she backs out of her date to the Christmas Eve dance with Andy. Betsy reconciles Andy and Polly, at least for the moment. The question of whether anything will spark between Andy and Betsy in the future remains an open question at the end of this episode in the Andy Hardy tale. The Hardy series is a forefather and foremother of American television sitcoms.

4. Romanticism is one of the cultural themes at the heart of Love Finds Andy Hardy not to mention other Hollywood films. All three girls, Polly, Cynthia, and Betsy, really do want Andy Hardy. One of the things one imagines those young people, particularly of the female of the species, who went to see the Andy Hardy films found compelling was the romanticism of the film, a representation that fed into their own romantic fantasies in their lives.

5. Is the reference to Brigham, Canada and polygamy in Love Finds Andy Hardy a sly reference to Mormonism?

6. Though Love Finds Andy Hardy was released in June it has a Christmas theme to it and even has a kind of Christmas miracle as part of its denouement. And then there is that fascinating the Hardy clan wishes you a Merry Christmas short included on the DVD.

1. There are a several cultural antinomies or binaries at the heart of Love Finds Andy Hardy. The first is the antinomy between small-town Carvel and big city New York City, which is mentioned but never seen in the film. It will be in a later installment in the Andy Hardy series. There is the binary between the historical past of Judge Hardy (Lewis Stone) and the historical present of Andy Hardy (Mickey Rooney). Judge Hardy's more traditional world is a world without aeroplanes, a world of covered wagons, a world where you don't buy on credit, and a world of correct speech. Andy's modern world is a world of aeroplanes, of cars, of buying on credit, of telegrams, of telephones, of ham radios, and the latest in hip popular speech. There is the antinomy between Andy's girlfriend Polly (Ann Rutherford), the Midwest every woman who is economic with her kisses, who swims with Andy, and who takes the long way home through the woods with Andy, and Beezie's (George Breakston) girlfriend, who Andy is looking after while Beezie is away, Cynthia (Lana Turner), who, as Andy says, wants to kiss all the time, who doesn't go swimming because she doesn't want to ruin her hair, and sees the long way home as an excuse to kiss some more. There is the binary between the uppitiness of Cynthia and the Midwest down homeness of small town Polly.

2.Betsy (Judy Garland) is the youngest of the three loves who find Andy Hardy. Betsy is, as she says, the in-between girl, the unglamourous girl. She is too young for Andy to take seriously as a love interest though clearly Betsy is smitten with Andy knowing about him before she even arrives in Carvel from the big city. Betsy becomes a "Cinderella" in Carvel, becomes a kind of grown up in Carvel, thanks to the grown up gown she wears to the Christmas Eve dance Andy takes her to and her acceptance by others at that dance during which she performs two songs with the band and gets to lead the grand march at the Christmas Eve dance.

3. Betsy, the in-between girl, is the girl who makes everything right for Andy by film's end. Love Finds Andy Hardy is a comedy of manners and misunderstandings. It is Betsy who sets the misunderstandings right by film's end. She convinces Cynthia that the car Andy is going to take her to the Christmas Eve dance in is a jalopy, a jalopy that is below the uppity Cynthia, so she backs out of her date to the Christmas Eve dance with Andy. Betsy reconciles Andy and Polly, at least for the moment. The question of whether anything will spark between Andy and Betsy in the future remains an open question at the end of this episode in the Andy Hardy tale. The Hardy series is a forefather and foremother of American television sitcoms.

4. Romanticism is one of the cultural themes at the heart of Love Finds Andy Hardy not to mention other Hollywood films. All three girls, Polly, Cynthia, and Betsy, really do want Andy Hardy. One of the things one imagines those young people, particularly of the female of the species, who went to see the Andy Hardy films found compelling was the romanticism of the film, a representation that fed into their own romantic fantasies in their lives.

5. Is the reference to Brigham, Canada and polygamy in Love Finds Andy Hardy a sly reference to Mormonism?

6. Though Love Finds Andy Hardy was released in June it has a Christmas theme to it and even has a kind of Christmas miracle as part of its denouement. And then there is that fascinating the Hardy clan wishes you a Merry Christmas short included on the DVD.

Monday, 23 July 2018

The Books of My Life: The Cambridge Introduction to Russian Literature

As someone interested in Russian history, Russian culture, and Russian literature I greatly enjoyed reading Caryl Emerson's The Cambridge Introduction to Russian Literature (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008, 2009).

Emerson's book is neither exhaustive or encyclopedic. If you are looking for an excellent if somewhat out of date encyclopedia of Russian literature I recommend Handbook of Russian Literature edited by Victor Terras and published by the Yale University Press in 1985. What Emerson's introduction is, is first, a study of Russian literature grounded in, though not in a literalist or fundamentalist way, a Bakhtinian approach to culture which emphasises time and space. Second, it is a study of several culturally important Russian ideas--the Russian word, Russian space, and faces. Third, it is an exploration of Russian cultural types--righteous persons, fools, frontiersmen, rogues and villains, misfits, and heroes. Fourth, it is an exploration of Russian narrative forms--saints, religious and secular, folk tales, folk epics, Faustian tales, miracle tales, magical tales, and legal tales. Finally, it is an exploration of how those ideals, types, and tales, played themselves out in Russian and Soviet literature in the eighteenth century, the romantic nineteenth century, the realist nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the symbolist and modernist twentieth century, the socialist realist twentieth century, and, if briefly, the postmodernist late twentieth and twenty-first century.

There were a number of things I liked about Emerson's book. I greatly enjoyed her exploration of the cultural continuities between eighteenth, nineteenth, and early twentieth century Russian literary culture and twentieth century Soviet literary culture. I enjoyed Emerson's discussion of Andrei Bely's Petersburg, Mikhail Bulgakov's Master and Margarita, and Yevgeny Zamyatin's We, as representative of symbolist and modernist Petersburg, Moscow, and dystopian cultural cityscapes in early twentieth century Russia and the USSR. I enjoyed Emerson's exploration of how Soviet socialist realism was, simultaneously, something old and something new, though I sometimes felt she overemphasised the newness of Soviet socialist realism.

Highly recommended. Perhaps one day someone will explore, if they already haven't, how Ayn Rand's sense of self as a secular saintly hero, how for her any other social formation other than free market libertarianism was demonic or Faustian, and how her narcissism, a product in part of late nineteenth and early twentieth century Nietzschean romanticism, are at the heart of her economic thought and literary texts. I suppose we might be able to throw Igor Stravinsky and Vladimir Nabokov into the same pot.

Emerson's book is neither exhaustive or encyclopedic. If you are looking for an excellent if somewhat out of date encyclopedia of Russian literature I recommend Handbook of Russian Literature edited by Victor Terras and published by the Yale University Press in 1985. What Emerson's introduction is, is first, a study of Russian literature grounded in, though not in a literalist or fundamentalist way, a Bakhtinian approach to culture which emphasises time and space. Second, it is a study of several culturally important Russian ideas--the Russian word, Russian space, and faces. Third, it is an exploration of Russian cultural types--righteous persons, fools, frontiersmen, rogues and villains, misfits, and heroes. Fourth, it is an exploration of Russian narrative forms--saints, religious and secular, folk tales, folk epics, Faustian tales, miracle tales, magical tales, and legal tales. Finally, it is an exploration of how those ideals, types, and tales, played themselves out in Russian and Soviet literature in the eighteenth century, the romantic nineteenth century, the realist nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the symbolist and modernist twentieth century, the socialist realist twentieth century, and, if briefly, the postmodernist late twentieth and twenty-first century.

There were a number of things I liked about Emerson's book. I greatly enjoyed her exploration of the cultural continuities between eighteenth, nineteenth, and early twentieth century Russian literary culture and twentieth century Soviet literary culture. I enjoyed Emerson's discussion of Andrei Bely's Petersburg, Mikhail Bulgakov's Master and Margarita, and Yevgeny Zamyatin's We, as representative of symbolist and modernist Petersburg, Moscow, and dystopian cultural cityscapes in early twentieth century Russia and the USSR. I enjoyed Emerson's exploration of how Soviet socialist realism was, simultaneously, something old and something new, though I sometimes felt she overemphasised the newness of Soviet socialist realism.

Highly recommended. Perhaps one day someone will explore, if they already haven't, how Ayn Rand's sense of self as a secular saintly hero, how for her any other social formation other than free market libertarianism was demonic or Faustian, and how her narcissism, a product in part of late nineteenth and early twentieth century Nietzschean romanticism, are at the heart of her economic thought and literary texts. I suppose we might be able to throw Igor Stravinsky and Vladimir Nabokov into the same pot.

Sunday, 22 July 2018

The People of the Light and the Demons of the Dark: Manicheanism in Contemporary America

For whatever reason, biological or cultural, humans tend to

think in either/or or binary terms. Since humans settled down into agricultural

or trading communities and multiplied as a result, human groups whether clans,

tribes, city-states, kingdoms, states, or nations, have had to, in order to

define themselves, have had to, in order to identify themselves corporately as a

group, had to define themselves against some other.

Generally such us and them distinctions code the us as good

and the not us, the other, in more negative hues. The ancient world, for

instance, had its Athenians and its Spartans and its Greeks and its

"barbaros". The Mediaeval era had its Orthodox Christians and Roman

Catholic Christians, its Christians and Jews, and its Christians and Muslims.

The modern era had its English and Dutch, its English and Spanish, its English

and French, and its French and Germans.

The United States, a European settler society, has also been

characterised by a manichean binarism and it was characterised by Manichean

binarism even before it was born. The Colonial era, for instance, had its

Protestants and Catholics and its English and French. The American 19th century

had its WASP "true Americans" and its Catholics, Mormons, Masons,

Chinese, Japanese, Irish, and its Southern and Eastern European un Americans.

Catholics, Mormons, Masons, and Chinese faced mob violence and death--an

extermination order was issued against Mormons and the Mormon leader and

prophet Joseph Smith was assassinated in the mid 19th century--during the era

while Southern and Eastern Europeans were, in the late 19th and early 20th

century, limited from entering the sacred precincts of WASP America. Chinese

and Japanese weren't even allowed in the US at all thanks to agreements between

political elites. In the early and mid 20th century Jehovah's Witnesses faced

mob violence because of their refusal to salute the holy and sacred American

flag, symbol of the American religion of nationalism. In the late 19th century

such "un-Amrican groups" as communists, anarchists, and socialists

were attacked, targeted by the forces of order, and found guilty of

insurrection in a series of American show trials.

Some

Americans want to believe that such violence, verbal and physical, ended with

World War II. In really, however, it didn't. In retrospect, the depression era

and particularly the World War Two era and 1950s, which ended in 1964, seemed like

an era of American consensus and the end of ideology to those Americans living

in the age of the so called greatest generation and the early years of the baby

boom generation. In truth, the era from the New Deal to the end of the Great

Society actually was, to some extent, an era of consensus and an end to

ideology if one forgets that the John Birch Society and Southern evangelicals

were building their strength and biding their time during that era. With the

cultural war of the 1960s, which ended in the early 1970s, however, the culture

wars came back with a vengeance in the US as the hard hat "silent

majority" attacked countercultural protesters in the streets of New York City.

By the 1970s

and 1980s, stimulated by Supreme Court decisions which restored the separation

of religion and state and which legalised abortion in the US, Southern White

evangelicals came back with a vengeance. Southern White evangelicals became an

important fraction of the Republican Party in the era thanks to Richard Nixon's

and Keven Phillips's Southern strategy and thanks to the Republican Party morphing,

in part, into latter-day Dixiecrats with significant managerial support. The

Democrats, on the other hand, declined in the old Dixiecrat South where they

once held and monopoly on power and increasingly carried the flag for

postmodern elites, who were cultural liberal but economically neoliberal, and a

host of identity groups including, increasingly, Blacks, Hispanics, and Asians.

The 1970s through the 2000s saw a culture war on several fronts in the US including over religion in the public schools, abortion, art, freedom of speech, movies, television, religion in the public sphere. Increasingly, as recent data show, Democrats and Republicans divided, intermarrying less and living together in the same geographics less. Today, once again, America is, as it was before the Civil War and the era of Jim Crow, politically and ideologically divided.

I have spent the last two years doing ethnography on social media, particularly on Facebook. While I wouldn’t argue that what I have seen and heard on Facebook is a random sample I do think it is representative of what is happening on the political and cultural levels in the US at the moment. What I have found among Democrats on Facebook is patented binarism. Democratic posters, for instance, have already anti-anointed the profane Trump as the worse president in history as though the notion of the best and worst presidential poll is akin to an ideological beauty contest while at the same time expressing a limited nostalgia for the New Deal era of FDR, the Great Society era of LBJ, and the, though this is elided, the neoliberal eras of Clinton and Obama, years that saw the end of welfare as the New Deal and the Great Society knew it and the end of the firewall between commercial and investment banks as the New Deal, Great Society, and even the Reagan and Bush the First years knew it.

I found that Democratic posters divide the American world into “us” and “them”, those who are with us and those who fellow travel with us, and those who are not with us and who, as a result, are damned to the hells of idiocy, moronicity, racism, sexism, and regress. The biggest demonic enemy by far at this moment for most Democrat ideologues and demagogues and their groupies is clearly the Russians. For them the profane Russians stole the election from Hillary Clinton and brought their favourite or the man they have something on, Donald Trump, to power.

The 1970s through the 2000s saw a culture war on several fronts in the US including over religion in the public schools, abortion, art, freedom of speech, movies, television, religion in the public sphere. Increasingly, as recent data show, Democrats and Republicans divided, intermarrying less and living together in the same geographics less. Today, once again, America is, as it was before the Civil War and the era of Jim Crow, politically and ideologically divided.

I have spent the last two years doing ethnography on social media, particularly on Facebook. While I wouldn’t argue that what I have seen and heard on Facebook is a random sample I do think it is representative of what is happening on the political and cultural levels in the US at the moment. What I have found among Democrats on Facebook is patented binarism. Democratic posters, for instance, have already anti-anointed the profane Trump as the worse president in history as though the notion of the best and worst presidential poll is akin to an ideological beauty contest while at the same time expressing a limited nostalgia for the New Deal era of FDR, the Great Society era of LBJ, and the, though this is elided, the neoliberal eras of Clinton and Obama, years that saw the end of welfare as the New Deal and the Great Society knew it and the end of the firewall between commercial and investment banks as the New Deal, Great Society, and even the Reagan and Bush the First years knew it.

I found that Democratic posters divide the American world into “us” and “them”, those who are with us and those who fellow travel with us, and those who are not with us and who, as a result, are damned to the hells of idiocy, moronicity, racism, sexism, and regress. The biggest demonic enemy by far at this moment for most Democrat ideologues and demagogues and their groupies is clearly the Russians. For them the profane Russians stole the election from Hillary Clinton and brought their favourite or the man they have something on, Donald Trump, to power.

I found that

you can’t really have a dispassionate and empirically grounded discussion with

these increasingly manichean Democrats any more than you can argue with the Westboro Baptist Church, libertarians, or Trumpians. Only the content between these various groups is different, their form is the same. For instance, if you point out,

assuming that twelve or so Russian operative attempted to create chaos on

social media in the days leading up to the 2016 election, that this doesn’t

prove that Clinton beat Trump in the battleground states like Wisconsin, Ohio,

Pennsylvania, and Florida, they ignore you. If you point out that a recount

asked for by the Green Party candidate Jill Stein, 2016’s Ralph Nader, another

in a long list of individuals who stabbed poor Hillary in the back, found that

Trump actually gained votes in Wisconsin during the recount, they ignore you. If you point out that the US and Russia are great powers who have interfered in

the politics and economics of a host of sovereign nations since the end of

World War II if not before, they ignore you. If you point out that the US

interfered in the Russian election of 1996, they ignore you. If you point out that Democrats and

Republicans are both neoliberal, they don’t care. For the manichean Democrats

the US, well the Democrat led US and its FBI and CIA fellow travellers are the good guys while

the evil Russkies are the black hated really bad guys. As is almost always the case, after all, culture and ideology create "reality"for most people.

Tuesday, 17 July 2018

The Books of My Life: Inside the Tardis

What we read, just like what we are intellectually interested in, is, in large part, a product of what we value regardless of who we are. I have been a long time watcher of Doctor Who so it is not surprising that one of the books I would get around to reading at some point is James Chapman's Inside the Tardis: The Worlds of Doctor Who (London: Tauris, revised edition, 2013).

Chapman, a film and television historian who has also written on the James Bond films and The Saint and The Avengers television series's, has written a book that should be, in many ways, a model of how one should write a book on a television series, particularly one as historically and culturally significant as Doctor Who. Chapman's book is grounded in historical analysis, genre and subgenre analysis, the analysis of discourse surrounding Doctor Who of critics and fans, and, most significantly, at least for Doctor Who from 1963 through the 1970s, in archival work at the BBC Written Archives Centre in Reading. As a result Chapman's book nicely puts Doctor Who from the first doctor to the eleventh in broader economic, political, technological, institutional (BBC, British television), cultural, geographic (UK), and demographic contexts.

Chapman's exploration of the BBC Written Archives gives Inside the Tardis a richness and texture that is missing from most books on TV shows written by the devotees of the donut hole or crystal ball textualism who generally eschew archival work, interviews with personnel involved in the making television shows, and qualitative and quantitative analysis of how viewers actually read the television shows they watch that unfortunately dominates film, television, and literary analysis these days. Chapman's work in the BBC archives not only gives richness and texture to his analysis of Doctor Who. It also allows him to put to rest several mythic sacred cows that have become common place in Doctor Who criticism, such as that, for example, which puts the reason for the demise of Doctor Who in 1969 solely at the feet of BBC One Controller Michael Grade. Chapman rightly sees the freezing of the BBC's license fee, the transformation of programming practises, the rise of new technologies, inflation, and Thatcherism as playing the leading roles for why Doctor Who was put on hiatus in 1989.

There is one downside to Chapman's book. It is a pity that the 1980s archives were not available for study at the time of Chapman's research and writing. Hopefully either Chapman or some other enterprising scholar can rectify this in the future.

I want to conclude by giving Chapman's book, despite its limitation, my highest recommendation. I not only recommend it to fans of Doctor Who but for those looking for an example of how to write and write in a jargon free way about historically and culturally significant television programmes like Doctor Who. May Doctor Who live for another fifty years.

Friday, 13 July 2018

The Books of My Life: Mikhail Bulgakov

As I mentioned earlier, I have long been interested in Russian culture, and particularly Russian literature and Russian film. It is not surprising, then, that I would end up reading a new biography on one of my favourite Russian writer, one of my favourite writers in general, Mikhail Bulgakov.

Julie Curtis's Mikhail Bulgakov (London: Reaction, 2017) is everything a brief biography aimed at a wider audience should be. Curtis, who teaches Russian literature at Wolfson College, the University of Oxford, and who has written extensively on Bulgakov, tells the tale of Bulgakov's life, briefly summarises a number of Bulgakov's plays, short stories, novellas, and plays, and succinctly puts Bulgakov's life in to its broader economic, political, and cultural contexts, all in a jargon free way. Other plusses of Curtis's biography of Bulgakov include the fact that Curtis's book is one of the first English language biographies of Bulgakov that is grounded in archival materials that have only recently been "rediscovered" in Soviet archives including those of the OGPU, one of the predecessors of the KGB, and it contains several excellent and relevant photographs of Bulgakov, his wives, his siblings, his friends, and the home where he grew up in Kiev.

For those of you, by the way, who are interested in reading what many consider to be Bulgakov's masterpiece, Master and Margarita, Curtis recommends three translations, those of Hugh Aplin, Diane Burgin and Katherine Tiernan O'Connor, and Michael Glenny, the last despite its flaws. She does not recommend the translation by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky. I recommend reading Bulgakov's Master and Margarita, The White Guard, The Fatal Eggs, and The Heart of a Dog either in the original or in translation as soon as you can if you already haven't.

Highly recommended.

Julie Curtis's Mikhail Bulgakov (London: Reaction, 2017) is everything a brief biography aimed at a wider audience should be. Curtis, who teaches Russian literature at Wolfson College, the University of Oxford, and who has written extensively on Bulgakov, tells the tale of Bulgakov's life, briefly summarises a number of Bulgakov's plays, short stories, novellas, and plays, and succinctly puts Bulgakov's life in to its broader economic, political, and cultural contexts, all in a jargon free way. Other plusses of Curtis's biography of Bulgakov include the fact that Curtis's book is one of the first English language biographies of Bulgakov that is grounded in archival materials that have only recently been "rediscovered" in Soviet archives including those of the OGPU, one of the predecessors of the KGB, and it contains several excellent and relevant photographs of Bulgakov, his wives, his siblings, his friends, and the home where he grew up in Kiev.

For those of you, by the way, who are interested in reading what many consider to be Bulgakov's masterpiece, Master and Margarita, Curtis recommends three translations, those of Hugh Aplin, Diane Burgin and Katherine Tiernan O'Connor, and Michael Glenny, the last despite its flaws. She does not recommend the translation by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky. I recommend reading Bulgakov's Master and Margarita, The White Guard, The Fatal Eggs, and The Heart of a Dog either in the original or in translation as soon as you can if you already haven't.

Highly recommended.

Thursday, 12 July 2018

The Books of My Life: Totalitarianism

Abbott Gleason’s Totalitarianism: The Inner History of the

Cold War (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995) is a largely dispassionate

exploration and analysis of the origins, life, and ups and downs, of the idea

“totalitarian” since it arose in the 1920s as an apologetic

and polemical way to “describe” fascist Italy. As Gleason notes the term became

more prominent in the 1930s, particularly in application to Nazi

Germany, became a prominent way to characterise the USSR during the Cold War,

declined in academic usage after the cultural revolution in the 1960s, was

resurrected by neoconservative polemicists in the era from Reagan to the fall

of the USSR, an era of increased tension between the great powers of the US and USSR, and has become somewhat popular in

post-Soviet Russia, in part, as a way to assuage feelings of guilt.

There are a number of things I took away from Gleason’s informative

book though I am not sure how happy he would be about what I took away from it.

Gleason’s book shows that the term “totalitarian” has been, particularly since

the 1940s, one of those key symbols that Cultural Anthropologists sometimes

talk about, symbols that reveal much about their societies and cultures in general because they interact with, interweave with, intertwine with, and give meaning to a host of other political, economic, and cultural symbols in those societies and cultures. As Gleason’s book shows, the key symbol “totalitarian”

became politically, economically, and culturally central during the Cold War in the West and particularly to the United States. Currently, the ideologically loaded term "dictatorship" seems to have replaced "totalitarian" in demagogic discourse.

As a key symbol in the West and the US “totalitarian” worked or functioned,

particularly on the political policy, journalistic, and popular

levels, in a Manichean "us" versus them way. For many polemical

users of the symbolic term "totalitarian", the West and the US, were “democratic” while Fascist

Italy, Nazi Germany, and the USSR, or Stalin era USSR, were “totalitarian”. For

many polemical users of the symbolic term we, the“free nations”, were “free”, while they,

the "totalitarian" states, were not. For many polemical users of the term we, the "free" nations were "good" while they, the "bad" states, were not. For

many polemical users of the term they, the "totalitarian" nations, “brainwashed” their

subjects, while we, the “free nations”, respected and treasured "freedom of "speech" and "freedom of thought". For many polemical users of the term we, the "free nations" are

“civilised” while they, the "totalitarian" states, are "brutal" and "thuggish" bringers of "terror".

For many polemical users of the term we “democracies” and “free

nations”, respect human rights while they, "totalitarian" states, did not. Such

symbolic binary formulations like these, by the way, miss several things. They

miss that even during the more egalitarian days of American New Deal liberalism

and the post-World War II Atlee era of Labour dominance in the United Kingdom,

“free nations” were—and still are—oligarchic. They miss that every group or

society that survives socialises its "citizens" in both coercive and more non-coercive ways, that

some societies or groups socialise more intensely while others socialise less

intensely, and that all human groups and societies socialise for conformity.

Gleason shows that the tern “totalitarian” has been used

polemically and academically in inconsistent ways. For some Nazi Germany was “totalitarian”.

For some the USSR was “totalitarian”. For some Nazi Germany and the Stalin era Soviet

Union were “totalitarian”. For some Japan, Argentina, Spain, and Portugal were,

during their years of military rule, “totalitarian”. For others these nations

were “authoritarian”. The latter, claimed those polemicists, many of who were ensconced in government positions, who made the distinction

between “totalitarian” and “authoritarian” regimes, assumed that “totalitarianism”

was new and that “authoritarian” regimes could be transformed while "totalitarian" ones could not be transformed. For some, as early as the 1930s, not only were Nazi Germany and the

USSR “totalitarian”, so was US New Deal liberalism. Needless to say, the

demonisation of American liberalism has become increasingly prominent in 21st

century American neoconservative polemical circles. Ignoring the "terror" of "authoritarian" regimes was

functional in a world divided into us, the "free world", those who are

with us ("authoritarians" who will become more like us over time), and them, the "totalitarian" Communist bloc.

Gleason shows that the symbolic term “totalitarian” has been

used in a largely ahistorical and hence problematic way. Those who use the term miss that, as Max

Weber noted, that supposedly “rational”

bureaucracies are one of the central characteristics of a modernity that became

dominate in the modern West, including in the USSR, and remains a central component in

a postmodernity brought about, in large part, by the advent of new digital

communications technologies which became important in the postmodern West. In the final analysis, I would argue, it is best to see “totalitarianism”

as the modern form of "autocracy" rather than as something new as many polemicists would have it. The fact that so

many of those, whether of the polemical or more academic variety, used the

"totalitarian" use as a synonym for "despotism" and "autocracy" strongly suggests that "totalitarianism" was not new, despite the protestations of some, and that it was simply the old "autocracy" and "despotism" dressed up in modern demagogues clothing. The "autocratic" modern USSR, it turns out, by the way, was unable to adapt to the new postmodernist realities of globalisation and digital communications media. Given all this, I think we have to conclude, that the symbolic term "totalitarian", was, for many Western polemicists, consciously or unconsciously, a means to strike fear into the emotion laden hearts and minds of the masses in an era of modern mass propaganda and continuing great power competitions.

Fascinating book. Highly recommended.

Fascinating book. Highly recommended.

Saturday, 7 July 2018

The Books of My Life: Thinking With History

I have long had an interest in social and cultural theory, historiography, culture, and historical change and dynamics, particularly the coming of modernity and postmodernity. For all these reasons Carl Schorske's Thinking With History: Excursions in the Passage to Modernity (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1998) was a book I seemed fated to read at some point.

Schorske's book works on several levels. One one level Schorske explores how nineteenth European intellectuals, particularly, English, Scottish, French, German, and, more particularly Austrian intellectuals--intellectuals like Voltaire, Adam Smith, Fichte, Engels, Baudelaire, Nietzsche, Bachofen, Burkhardt, Richard Wagner, William Morris, Mahler, Kimt, Camillo Sitte, Otto Wagner, Adolf Loos, Karl Kraus, and Freud--confronted a modernity driven particularly by industrialisation. On another level Schorske explores the golden age, radiant future, and ahistorical historical ways that English, Scottish, German, and particularly Austrian intellectuals responded to this modernity.

There were two things, things you don't often find in intellectual and academic texts, I really appreciated about Schorske's book. In an introductory chapter Schorske places his historical work in broader economic, political, cultural, demographic, and geographic contexts and rightly notes that history as a discipline has no subject matter, theory, or methodology peculiar to it. In the concluding chapter Schorske reflects on the cultural turn in the social sciences and humanities since the 1960s, something that underpins his analysis of European intellectuals and modernity, and the role history now plays in other academic "disciplines" like social and cultural anthropology, art, and sociology. These reflexive chapters, a reflexivity that should be the stock and trade of every intellectual and academic and should make intellectuals and academics more cautious than they often are, alone make Schorske's book worth reading even if one is not particularly drawn to European and particularly Austrian cultural history.

Schorske's book works on several levels. One one level Schorske explores how nineteenth European intellectuals, particularly, English, Scottish, French, German, and, more particularly Austrian intellectuals--intellectuals like Voltaire, Adam Smith, Fichte, Engels, Baudelaire, Nietzsche, Bachofen, Burkhardt, Richard Wagner, William Morris, Mahler, Kimt, Camillo Sitte, Otto Wagner, Adolf Loos, Karl Kraus, and Freud--confronted a modernity driven particularly by industrialisation. On another level Schorske explores the golden age, radiant future, and ahistorical historical ways that English, Scottish, German, and particularly Austrian intellectuals responded to this modernity.

There were two things, things you don't often find in intellectual and academic texts, I really appreciated about Schorske's book. In an introductory chapter Schorske places his historical work in broader economic, political, cultural, demographic, and geographic contexts and rightly notes that history as a discipline has no subject matter, theory, or methodology peculiar to it. In the concluding chapter Schorske reflects on the cultural turn in the social sciences and humanities since the 1960s, something that underpins his analysis of European intellectuals and modernity, and the role history now plays in other academic "disciplines" like social and cultural anthropology, art, and sociology. These reflexive chapters, a reflexivity that should be the stock and trade of every intellectual and academic and should make intellectuals and academics more cautious than they often are, alone make Schorske's book worth reading even if one is not particularly drawn to European and particularly Austrian cultural history.

Wednesday, 4 July 2018

The Books of My Life: The Doctors Are In

I have been watching Doctor Who for some time now. I have seen all of the episodes of the third Doctor, the fourth Doctor, the fifth Doctor, the sixth Doctor, the seventh Doctor, the War Doctor, the ninth Doctor, the tenth Doctor, the eleventh Doctor, and the twelfth Doctor, and am looking forward to seeing the upcoming episodes of the thirteenth Doctor beginning later this year. Graeme Burk's and Robert Smith's The Doctors Are In: The Essential and Unofficial Guide to Doctor Who's Greatest Time Lord (Toronto: ECW, 2015) covers all of the Doctors up to but not including the thirteenth, which continues to be a problem inherent to this and previous books by Burk and Smith given that Doctor Who is an open text.

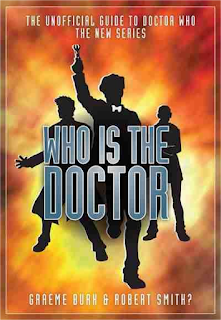

Some of the same problems that limited my enjoyment of Burk's and Smith's early book, Who is the Doctor, are present again in The Doctors Are In. While I have always accepted each Doctor Who episode for what it is--the social scientist and historian in me--Burk and Smith, on the other hand, like many other scholar fans, don't accept some episodes for what they are and instead rhapsodise normatively about what they would like those episodes to be. Thankfully, Burk's and Smith's polemics are not as evident in The Doctors Are In as they were in Who is the Doctor. Given the historical nature of The Doctors Are In the history quotient is ramped up while the polemic quotient is ramped down a bit making this a somewhat more enjoyable and enlightening read than the previous book for me.

Some of the same problems that limited my enjoyment of Burk's and Smith's early book, Who is the Doctor, are present again in The Doctors Are In. While I have always accepted each Doctor Who episode for what it is--the social scientist and historian in me--Burk and Smith, on the other hand, like many other scholar fans, don't accept some episodes for what they are and instead rhapsodise normatively about what they would like those episodes to be. Thankfully, Burk's and Smith's polemics are not as evident in The Doctors Are In as they were in Who is the Doctor. Given the historical nature of The Doctors Are In the history quotient is ramped up while the polemic quotient is ramped down a bit making this a somewhat more enjoyable and enlightening read than the previous book for me.

Monday, 2 July 2018

The Books of My Life: Who is the Doctor

I started watching the BBC's Doctor Who way back in the 1970s when Jon Pertwee and Tom Baker, probably still my favourite Doctor, were the Doctors. I continued to watch as Peter Davison, Colin Baker, and Sebastian McCoy succeeded Tom Baker as Doctor Who. At first I was hesitant to watch the Doctor Who reboot that began in 2005, but once I started watching it I fell in love with the show, again, to my relief.

I just spent the last month and a half rewatching and watching, in the case of the episodes from series seven on, all of the episodes of the Doctor Who reboot. As a result I was looking for an episode guide like The Television Companion: The Unofficial and Unauthorised Guide to Doctor Who by David Howe and Steven James Walker (Tolworth, England: Telos, 2003). Unfortunately, Graeme Burk's and Robert Smith's Who is the Doctor: The Unofficial Guide to Doctor Who the New Series (Toronto: ECW, 2012) is not it.

I found Who is the Doctor interesting, enlightening, eye rolling, and frustrating all at the same time. The summary sections for each episode are far too short. The reference sections raise questions about whether these references are emic, etic, or both raising the question, in turn, of whether references, if they aren't derived from primary source information, are valid. Some seem valid, others seem of questionable validity. Still others may have been ignored because not all references seem to have been derived from primary source analysis. The adventures in time and space sections were generally helpful particularly when they connected the reboot to the Classic Series, episodes of which I haven't seen since the 1970s and 1980s. The who is the Doctor sections are helpful. The stand up and cheer sections are interesting if largely subjective, which may or may not be a problem for some. The roll your eyes sections were likewise subjective and, as a result, were problematic, for me, given that they are sometimes grounded in a notion of realism that is not really an appropriate or valid "criticism" of a fictional television show. They were, for me, of the same variety and validity as those academic criticisms of Disney's Pocahontas (1995), which was not intended to be a historical documentary, as not being historically accurate enough. The trivia sections were OK. The opinion and second opinions sections were interesting but were often undermined, as is so often the case with fan criticism, by the assumption that the authors could have written better episodes than those who actually did write the episodes did making one wonder why they aren't writing each and every episode of Doctor Who. The psychic paper segments do a good job of exploring the similarities and differences between new Who and old. The biographies are far too brief.

Methodologically, I am more of an exegesis, hermeneutics, and homiletics sort of guy. In my book one must began with a critical analysis of a text, an exegesis of the text grounded in primary source material, with a summary of the text that is long enough to do it justice to it. Only then can one move on to hermeneutics or the interpretation of the text, to an exploration of what we think a text means on the basis of our exegesis. And only then can we finally move on to homiletics, to polemicising or engaging in apologetics over a text. Burk and Smith too often, it seems to me, start and end their "critical" analysis at the homiletic level and that is, at least for me, a problem.

Methodology isn't the only problem with Burk's and Smith's book. Their "criticisms" of Doctor Who's ethnic and racial lack of representation smacks of the same crystal ball tendency (the assumption and circular logic that you can learn anything you need to know about a text from the text itself) in much academic criticism these days that focuses exclusively on the text and largely jettisons any first order or primary source analysis of a television show or film. The book ends with series 6 while Doctor Who is now at series 11 making some of Burk's and Smith's "criticisms" problematic given that Doctor Who remains an open text.

As a result of all this, I will continue my search for a book on the new series of Doctor Who that is more like the Howe and Walker book, a book which seems to me, even with its faults, to be one of the best episode guides I have ever seen and read.

The Books of My Life: Red Flag Unfurled

If I was asked to recommend one book for

the interested intellectual, the advanced interested undergraduate, and the interested

graduate student on Russian and Soviet history it would be Ronald Suny’s Red

Flag Unfurled: History, Historians, and the Russian Revolution (London: Verso,

2017). Suny’s book does what far too few books do. On one level it explores the discourse, particularly the Western discourse and more specifically the American discourse, on

Russian and Soviet history and puts it into its proper broader economic, political, and cultural contexts. On another level, it offers a theoretical approach to

Russian and Soviet history and history in general that is analytic systematic, and critical rather than polemical and apologetic, as are so much post-1917 writing on Russian and Soviet history, as Suny notes. On still another level it

explores the history of Russia from the late Tsarist era to

the Stalin era. Highly recommended.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)